Many an architect has dreamed up visionary plans for city centers, but few have actually seen their designs come to fruition in a real live urban setting. And while many such unbuilt concepts are technically viable, others are wacky, fanciful or downright bizarre. These 13 vintage urban design ideas for the future, from perfectly symmetrical egalitarian communities to the egotistical demands of a deranged dictator, will probably never become reality – and in many cases, we’re better off that way.

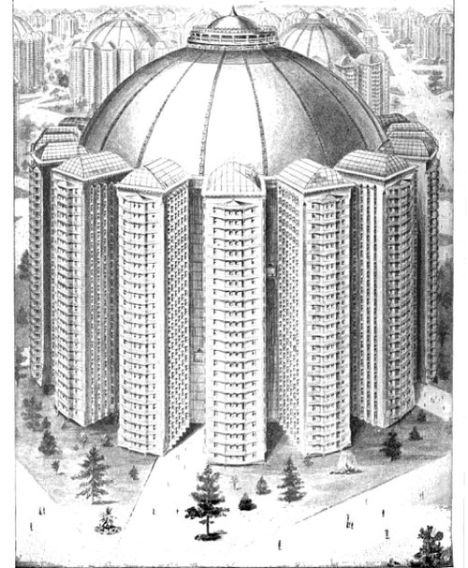

Gillette’s Metropolis

(images via: io9)

Before his name was inextricably connected to safety razors, King Camp Gillette had a utopian vision for the future which revolved around a waterfall-powered tiered city he dubbed ‘Metropolis’. All residents of this imagined city would have access to the same amenities including rooftop gardens in the perfectly round, precisely divided multi-functional buildings in which they would live, work, play and eat. Like many of Gillette’s ideas, the design never went anywhere, but it’s notably similar to many very modern 21st-century concepts for sustainable urban centers.

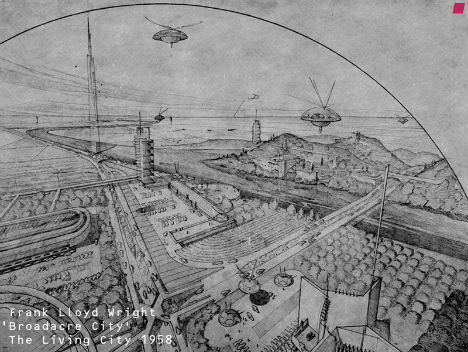

Broadacre City

(images via: mediaarchitecture.at)

Like Gillette’s Metropolis, Broadacre City was meant to be an urban utopia. But when renowned architect Frank Lloyd Wright imagined the picture-perfect society of tomorrow, he saw not highly compact and efficient high-rises, but sprawling self-sustainable homesteads. Originally conceived in 1932, Broadacre City puts each homeowner in a self-built single-family home on an entire acre of land brimming with gardens. Complete with multiple cars per family, it would almost be an accurate prediction of future suburbia if not for the airplane in every front yard.

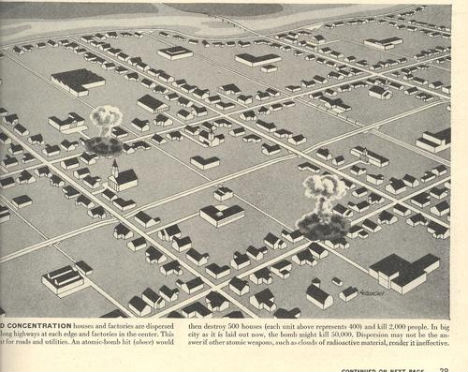

Atomurbia

(image via: io9)

If giving each and every family in America an acre of land seems impossible, imagine what life would be like if ‘Atomurbia’ had come to pass. This concept, published in a 1947 issue of Life magazine, detailed how to atomic bomb-proof America by spreading the population across the land in a geometric grid and relocating all industry into underground structures so that any single bomb would do a minimum of damage. The whole plan would have cost a measly 5 trillion dollars in today’s currency, and the authors – atomic scientists from Chicago – thought it could be pulled off within a decade.

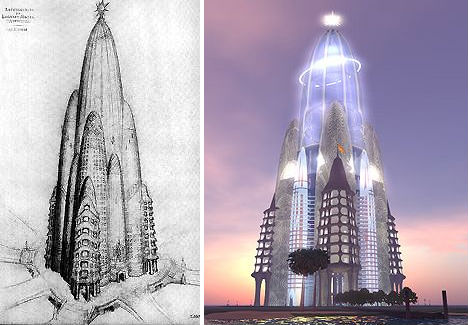

Hotel Attraction

(images via: wikimedia commons)

Antoni Gaudi’s architecture defines Barcelona, Spain even today with its fluid curves, reflective surfaces and organic shapes – but it would stick out like a sore thumb in the comparatively staid cityscape of Manhattan. Perhaps that’s what he had in mind for ‘Hotel Attraction’, commissioned in 1908 and also known as the Grand Hotel. The rounded, spaceship-like form would have risen in the exact spot where the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center were later built, but the idea was ultimately abandoned. Gaudi’s unrealized design was actually considered as a possibility for the Ground Zero memorial after the attacks of September 11th, 2001.

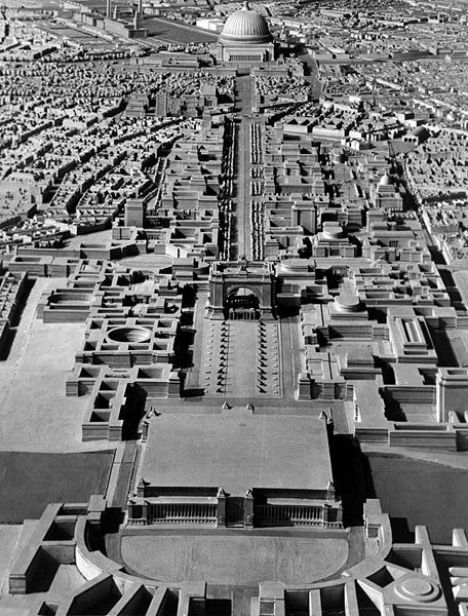

Welthauptstadt

(images via: wikimedia commons)

We all know that Adolf Hitler had many an ambitious plan that (thankfully) never came to pass – but few are aware of ‘Welthauptstadt’ (German for ‘World Capital’), the Fuhrer’s design for a new Berlin to be constructed after his expected victory in World War II. Taking elements from other empires around the world, Hitler imagined a broad ‘Avenue of Victory’ down the center as well as his very own ‘Arch of Triumph’. A test structure constructed in 1938 to determine whether Berlin’s marshy ground could have even held up such heavy Romanesque architecture (verdict: nope) still stands today.

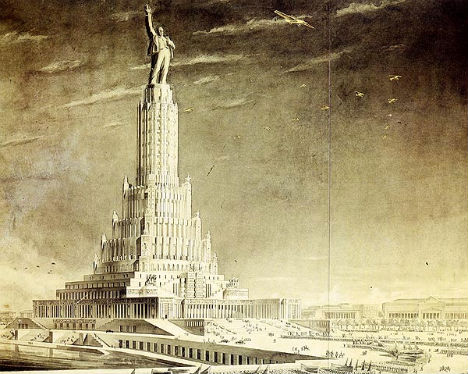

Palace of Soviets

(image via: adlhochcreative)

The Palace of Soviets would have been the world’s tallest structure at 100 meters high and crowned with a brightly lit hammer and sickle as a monument to Lenin on the site of the demolished Cathedral of Christ the Savior, if only the Nazis hadn’t invaded in 1941, putting a stop to construction. Its steel frame was disassembled for use in fortifications and bridges, and its foundations served as the world’s largest open-air swimming pool for a while before 1995 when the whole thing was filled in so that the cathedral could be rebuilt.

Ville Contemporaine

(images via: tommatthew)

The architect known as Le Corbusier was an essential figure in the development of what we now know as modern architecture, and his many theoretical urban design projects aimed to make life better for residents of cramped cities. Displeased with the chaos of big cities, Le Corbusier designed ‘Ville Contemporaine’ as an orderly home to three million people where housing, industry and recreation all occupied distinct areas connected by roads that emphasized the use of personal vehicles for transportation.

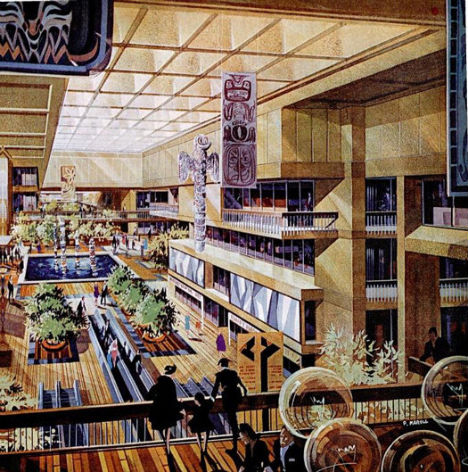

Seward’s Success

(images via: matthewspencer)

If it was Seward’s Folly to purchase Alaska from the Russian Empire in the first place, perhaps Seward’s Success – a huge climate-controlled, glass-enclosed city for 40,000 people – could have made up for it. Or not. Proposed in 1968 and nixed in 1972, this unbuilt community was dreamed up after the discovery of oil reserves at Prudhoe Bay, Alaska when developers imagined droves of people coming to the area. The crowning jewel of the perpetually 68-degree dome would have been a 20-story Alaskan Petroleum Center, surrounded by housing, offices, retail space and an indoor sports arena.

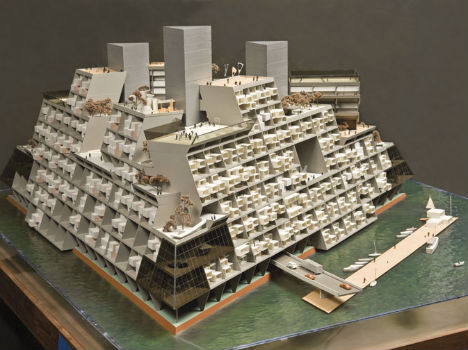

Triton City

(images via: a place to stand)

If not for a certain tell-tale 1960s aesthetic, Buckminster Fuller’s ‘Triton City’ could easily fit among today’s designs for floating eco-friendly cities. The futurist, architect and inventor was ahead of his time as usual when he imagined this tetrahedronal metropolis for Tokyo Bay, a seastead for up to 6,000 residents. Fuller wrote about the possibility of desalinating and recirculating seawater “in many useful and non-polluting ways” and using materials from obsolete buildings on land, which were hardly popular ideas at the time.

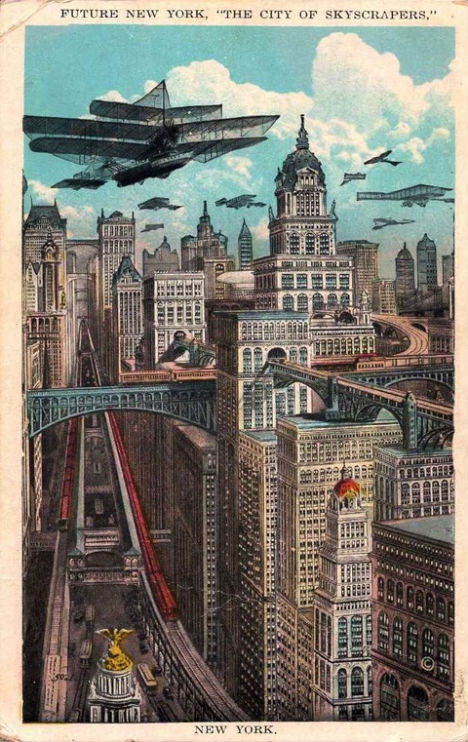

Future New York, “The City of Skyscrapers”

(images via: io9)

By 1925, many of New York City’s skyscrapers were already present, but futurists of the time envisioned not only a great deal more but a sort of aerial civilization complete with elevated train platforms and perhaps a rather unsafe number of aircraft flying around all at once.

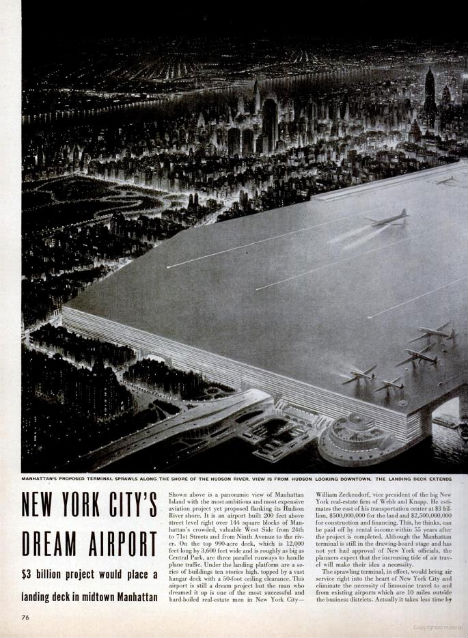

New York City’s Dream Airport

(image via: ptak science books)

All the airplanes in that 1925 postcard would definitely require a monumental airport in New York City, and what better location than right smack in midtown Manhattan? This concept for “New York City’s Dream Airport” featured an astonishingly large – and some say ugly – runway platform. But for all of the prime real estate that this monstrosity would have devoured, it seems as if it could only handle a handful of planes at a time with absolutely zero margin of error, sending errant planes straight into Central Park or the East River.

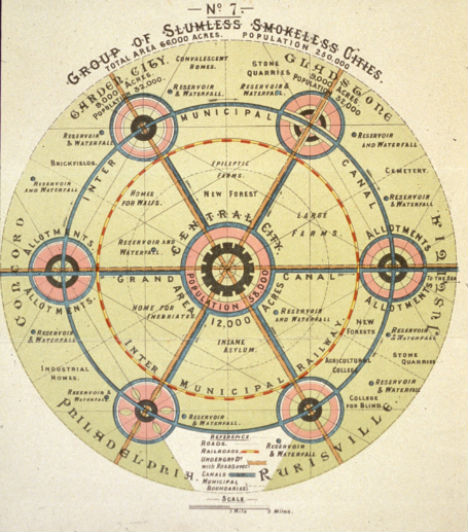

Slumless, Smokeless Cities

(image via: bigthink.com)

How do you build a city so egalitarian that slums are eliminated entirely, and nobody ever has to breathe in pollution? Sir Ebenezer Howard, the father of the garden city movement, believed that a careful layout with six satellite garden cities connected via canals to a densely populated central city would do the trick. Thoughtfully, the design included specially designated spaces for “Eplileptic Farms”, “Homes for Waifs”, “Homes for Inebriates” and an insane asylum.

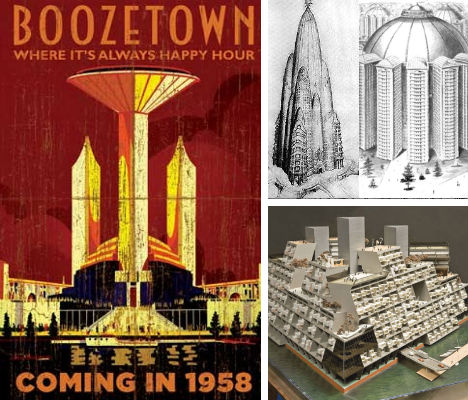

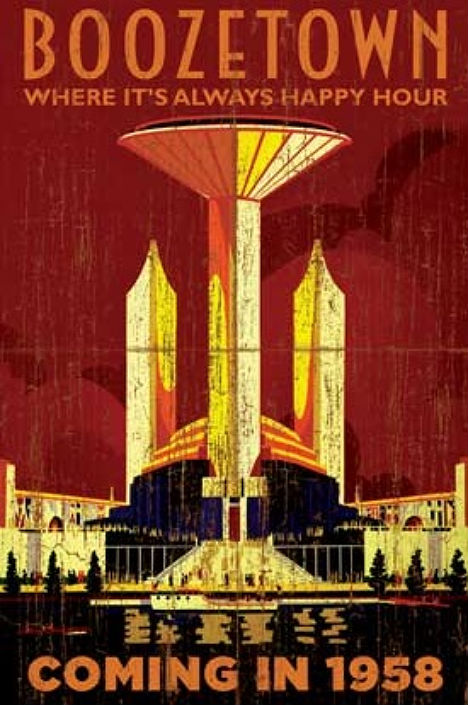

Boozetown

(images via: modern drunkard magazine)

“Just imagine a resort entirely centered on the culture of alcohol. A boozer’s paradise built expressly to facilitate drinking and the good times that naturally follow. Where the bars, clubs and liquor stores never close.” Mel Johnson’s ‘Boozetown’ was an entirely sincere proposal with street names like “Gin Lane” and “Bourbon Boulevard” that would have begun as a resort town in Middle America and eventually expanded into a full-sized adults-only city with permanent housing and its own suburbs. After many obsessed years of struggling for financing, Johnson gave up on his dream in 1960 and died in a mental hospital in 1962.